Early Settlements

Early Settlements

Following nearly a century of exploration of the New World by European explorers, the first permanent settlements began to appear in the area, which was originally part of the New Netherlands colony, in the early 1600s. By the 1640s, the New Netherlands was a thriving colony, with New Amsterdam as its capital, and in just a few decades it had expanded as far east as the Connecticut River and as far north as the St. Lawrence River. Records indicate that the first European to settle on the land where Fort Schuyler now stands was John Throckmorton (sometimes spelled Throgmorton), who obtained a license to settle on the peninsula which now bears his name on October 2, 1642. Over the next nearly 200 years, the property changed hands several times, as did the governments which controlled the land, transferring from Dutch, to British, and finally American rule. Map of New Netherlands, 1600s

By the early 1800s, New York was already a large city and home to over 200,000 people, boasting a large natural port, numerous shipyards, a major financial center, and having served as the United States’ first capital. Fortifications had already been constructed through Lower New York Harbor to defend against attack, and it was clear that the city’s eastern waterways needed similar defenses. Map of New York City, 1828

Fort Construction

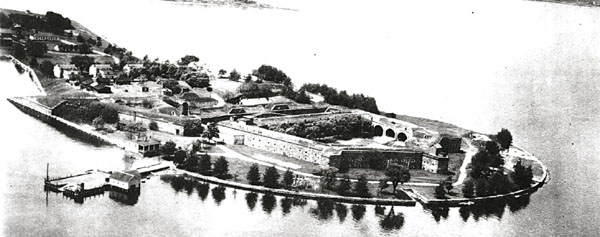

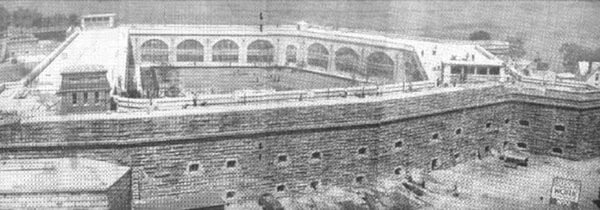

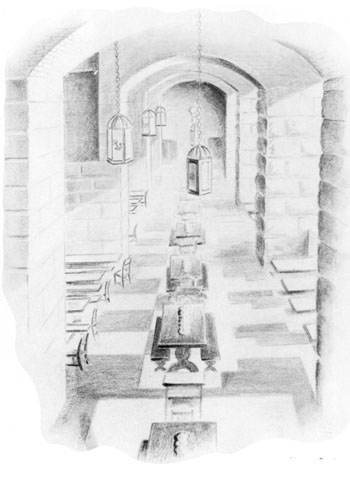

Construction of a fort on the Throggs Neck peninsula was first considered in 1818. A tract of 52 acres was purchased by the Federal Government from William Bayard in 1826 and construction of the fort began in 1833. In December 1845, the fort was ready for its armament of 312 seacoast and garrison guns, six field pieces, and 134 heavy guns. The installation of the armament was completed in 1856, and the fortification was named Fort Schuyler, in honor of General Philip Schuyler, who commanded the Northern Army in 1777, and whose conduct of the campaign is credited with laying the groundwork for the final defeat and capture of Bugoyne by Schuyler's successor, General Horatio Gates. The fort was built of granite brought from Greenwich, Connecticut in an irregular pentagon, and is said to have been the finest example in the United States of the French type of fortification for the purpose of both sea and land defense. It was built to accommodate a garrison of 1,250  men. Three full bastions at the salients of the waterfront, two demibastions flanking the gorge on the land front, and the bastioned coverface and covered way protecting the land side were armed for firing from every angle. The fort had two tiers of guns in casemates and one en barbette. The casemates had two embrasures each. Two gun embrasures and one howitzer embrasure were closed later on to make room for a torpedo casemate. On the land side, approach was over a drawbridge, after the manner of a medieval castle. This opened into a tunnel with narrow slits in each side for riflemen who would be able to pour a heavy fire upon any attacking force from that quarter.

men. Three full bastions at the salients of the waterfront, two demibastions flanking the gorge on the land front, and the bastioned coverface and covered way protecting the land side were armed for firing from every angle. The fort had two tiers of guns in casemates and one en barbette. The casemates had two embrasures each. Two gun embrasures and one howitzer embrasure were closed later on to make room for a torpedo casemate. On the land side, approach was over a drawbridge, after the manner of a medieval castle. This opened into a tunnel with narrow slits in each side for riflemen who would be able to pour a heavy fire upon any attacking force from that quarter.

Life at the Fort

On January 17, 1861, Fort Schuyler was garrisoned by engineers who occupied it until 1865, when it was turned over to artillerymen. During the Civil War, Fort Schuyler was also used as a prison to hold Confederate soldiers who were captured. It was during this time that the McDougall General Hospital at the fort, which was first built in 1862, was destroyed by fire. In 1868, the fort’s defenses were further enhanced with the addition of ten Rodman guns which were mounted in casemates on the first tier and these in turn were replaced later by eight-inch rifles. A medical report for 1868-1869, written by Assistant Surgeon C.B. White, who served in the fort’s hospital, contains a description of life at the post in that period. Officers and enlisted men lived in the casemates, the troops being quartered in eight rooms arranged in two tiers. Three windows in the rear, two windows and a door in front, and shutters over each ventilated the quarters so well that, despite the two fireplaces in each room, Surgeon White said, “to warm them properly in severe winters it has been necessary to revert to stoves.”

Laundresses and the families of married soldiers lived in a one story frame building which had 24 rooms and 12 sets of quarters. Officers were housed in south landward casemates in rooms similar to the men’s. There were no bathroom s except in the hospital. The men had a swimming place in summer. A shed over a well and pump within thirty feet of their quarters was a washroom for the enlisted men, and sinks in the front yard served the officers. Watercarts and barrels furnished well water which was “usually g

s except in the hospital. The men had a swimming place in summer. A shed over a well and pump within thirty feet of their quarters was a washroom for the enlisted men, and sinks in the front yard served the officers. Watercarts and barrels furnished well water which was “usually g ood.” The fort had natural drainage; excellent sewers emptied into large reservoirs, which were flushed regularly by the tides. So good was the sanitation that no deaths occurred within the period covered by Dr. White’s report. After October 12, 1870 when the artillerymen left, the post stood abandoned, but three years later work was begun on widening the terreplein of the north and east waterfronts for barbette batteries of fifteen-inch guns, leaving the emplacements unchanged on the south front and the demibastions of the gorge. This work was suspended in 1875 for the want of funds. It was also in 1875 that the New York State Merchant Marine Academy, which was later renamed SUNY Maritime College and now calls Fort Schuyler home, was established on

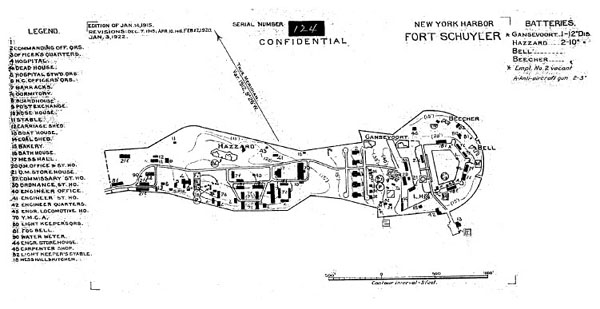

ood.” The fort had natural drainage; excellent sewers emptied into large reservoirs, which were flushed regularly by the tides. So good was the sanitation that no deaths occurred within the period covered by Dr. White’s report. After October 12, 1870 when the artillerymen left, the post stood abandoned, but three years later work was begun on widening the terreplein of the north and east waterfronts for barbette batteries of fifteen-inch guns, leaving the emplacements unchanged on the south front and the demibastions of the gorge. This work was suspended in 1875 for the want of funds. It was also in 1875 that the New York State Merchant Marine Academy, which was later renamed SUNY Maritime College and now calls Fort Schuyler home, was established on  the U.S.S. St. Mary’s. Fort Schuyler was regarrisoned by the infantry on June 28, 1877. Construction of more modern defenses began in 1896. Under this program, two ten-inch and two twelve-inch guns on disappearing carriages, two five-inch rapid fire guns, two fifteen-pounders, and battery commanders’ stations for the ten-inch and twelve-inch batteries were installed. The coast artillery now garrisoned the fort. In October, 1931, the fort was taken over by the Headquarters and Service Platoon and Company A, Twenty-Ninth Engineers, which were making a fire control map of New York and vicinity. This last garrison was officially withdrawn on May 1, 1934.

the U.S.S. St. Mary’s. Fort Schuyler was regarrisoned by the infantry on June 28, 1877. Construction of more modern defenses began in 1896. Under this program, two ten-inch and two twelve-inch guns on disappearing carriages, two five-inch rapid fire guns, two fifteen-pounders, and battery commanders’ stations for the ten-inch and twelve-inch batteries were installed. The coast artillery now garrisoned the fort. In October, 1931, the fort was taken over by the Headquarters and Service Platoon and Company A, Twenty-Ninth Engineers, which were making a fire control map of New York and vicinity. This last garrison was officially withdrawn on May 1, 1934.

Transfer to the Maritime Academy

As plans were being made by the Army to leave Fort Schuyler, local politicians were also beginning to make plans for the future use of the property. Since as early 1928, Fort Schuyler had been identified as a possible shore base for the Maritime Academy, so in 1932, when it was first announced that the Army would leave the fort, a proposal was made to Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.

There were many obstacles that had to be overcome, not the least of which was New York State’s own Robert Moses who wanted to convert the site into a city park, but ultimately, the Maritime Academy’s proposal prevailed, and a lease was signed by then President-elect Roosevelt in 1934.

Restoration

Restoration of Fort Schuyler as the permanent land base of the New York State Merchant Marine Academy began in the summer of 1934. While outwardly the main building remained much the same, with the exception of the roof, the interior was completely transformed.

One of the first jobs was the removal of 31,000 cubic yards of earth and sod from the roof and stripping the brick arches underneath. Several of these later had to be entirely rebuilt. Air ducts were set in and other openings for electrical fixtures were drilled through. The underside of the arches were then s andblasted and grouted to prevent leakage. Finally, a new concrete roof was put on and a parapet wall was constructed. Two duct chambers were erected on the roof for ventilation.

andblasted and grouted to prevent leakage. Finally, a new concrete roof was put on and a parapet wall was constructed. Two duct chambers were erected on the roof for ventilation.

Electric and water lines were brought from the mainland and a concrete chamber for electric, water, and steam lines was constructed around the inside of the fort. The steam lines run out of the building and across the road to the new heating plant, which was originally equipped with two boilers. Steam lines were also run from the heating plant to the individual houses occupied by members of the school staff. The oil was stored in huge tanks located in the old magazine forward of the fort proper. The most striking alteration of all was the bisection of the arches of the inner wall and the construction of a mezzanine floor all around the  fortification with the exception of the north-westerly end, where the mess hall was located (and which has since become the library). Here the story was eliminated in favor of a gallery with a staircase which gives access to the rooms beyond. The old floor of the fort was replaced with modern concrete to harmonize with the new mezzanine. The mess hall was floored with terrazzo. Steel frames and sashes were installed throughout and on both floors the spaces were partitioned off for classrooms, laboratories, drafting rooms, shops, administrative offices, and a library. Then, embrasures in the outer wall were relined with artificial stone and all stone work was sandblasted and repainted. The old barracks were reconditioned and fitted up as first class dormitories with tiled wash rooms, showers, and toilets. A vitally important job was the construction of the new pier for the accommodation of the training ship. When first constructed, the pier was 550 feet long and 40 feet wide with an approach 20 feet wide, and it was made of reinforced concrete equipped with mooring gear. In 1938, the New York State Merchant Marine Academy finally came ashore to their new home at Fort Schuyler. Since that time, Fort Schuyler has been home to the school, which has since been renamed the State University of New York (SUNY) Maritime College. Over the years, many changes have taken place on the college’s campus including the construction of numerous new buildings that serve as classrooms, dining facilities, dormitories, laboratories, a military base, staff offices/accommodation, and even the Throgs Neck Bridge, but Fort Schuyler remains the cornerstone of the college, and ser

fortification with the exception of the north-westerly end, where the mess hall was located (and which has since become the library). Here the story was eliminated in favor of a gallery with a staircase which gives access to the rooms beyond. The old floor of the fort was replaced with modern concrete to harmonize with the new mezzanine. The mess hall was floored with terrazzo. Steel frames and sashes were installed throughout and on both floors the spaces were partitioned off for classrooms, laboratories, drafting rooms, shops, administrative offices, and a library. Then, embrasures in the outer wall were relined with artificial stone and all stone work was sandblasted and repainted. The old barracks were reconditioned and fitted up as first class dormitories with tiled wash rooms, showers, and toilets. A vitally important job was the construction of the new pier for the accommodation of the training ship. When first constructed, the pier was 550 feet long and 40 feet wide with an approach 20 feet wide, and it was made of reinforced concrete equipped with mooring gear. In 1938, the New York State Merchant Marine Academy finally came ashore to their new home at Fort Schuyler. Since that time, Fort Schuyler has been home to the school, which has since been renamed the State University of New York (SUNY) Maritime College. Over the years, many changes have taken place on the college’s campus including the construction of numerous new buildings that serve as classrooms, dining facilities, dormitories, laboratories, a military base, staff offices/accommodation, and even the Throgs Neck Bridge, but Fort Schuyler remains the cornerstone of the college, and ser ves as the home of the Maritime Industry Museum.

ves as the home of the Maritime Industry Museum.

Fort Totten

Construction of a second fort, located directly opposite Fort Schuyler, in Bayside, Queens, was started in 1862. Together with this fort, named Fort Totten after the man who designed its water battery, New York City had a formidable defense against any threats arriving through the Long Island Sound. The original granite fort at Fort Totten was never completed, however, due to technological developments in artillery that led to its obsolescence before its construction could be completed, and it remains in its unfinished state to this day. Subsequent fortifications, including its Edicott Batteries were added, and Fort Totten remained an active U.S. Army base until 2000, at which time most of the land was turned over to New York City. Today, Fort Totten is a New York City park, and also contains a U.S. Army reserve command, NYPD and FDNY training and special operations facilities, a volunteer ambulance corps, and offices of local charitable organizations.